Kimberly E. Sawyer and Katherine E. MacDuffie

White Space

ABSTRACT

The case: A medical team considers withdrawal of artificial nutrition and hydration supporting a 6-month-old girl with complex cardiac disease, devastating neurological injury, and ongoing, unmanageable pain. Diffuse neurological injury and severe ischemia in all four limbs offers a bleak prognosis. This commentary is a companion to the original case report.

Read the Case Report

Commentary

ML’s story is tragic – for herself, her family, and her medical team.

When technologically advanced medicine fails to “rescue [a patient] intact from the conditions of her birth,” professionals must rely even more squarely on the foundation of good medicine – human-centered caring. While we do not disagree with Mr. Teti’s ethical analysis, we believe that ethics consultants can (and should) do more to support the medical team in achieving this foundational goal. Here, we describe an approach to this consult that centers on shared decision-making between ML’s medical team and her family, and provides suggestions of other caring ways to support all involved.

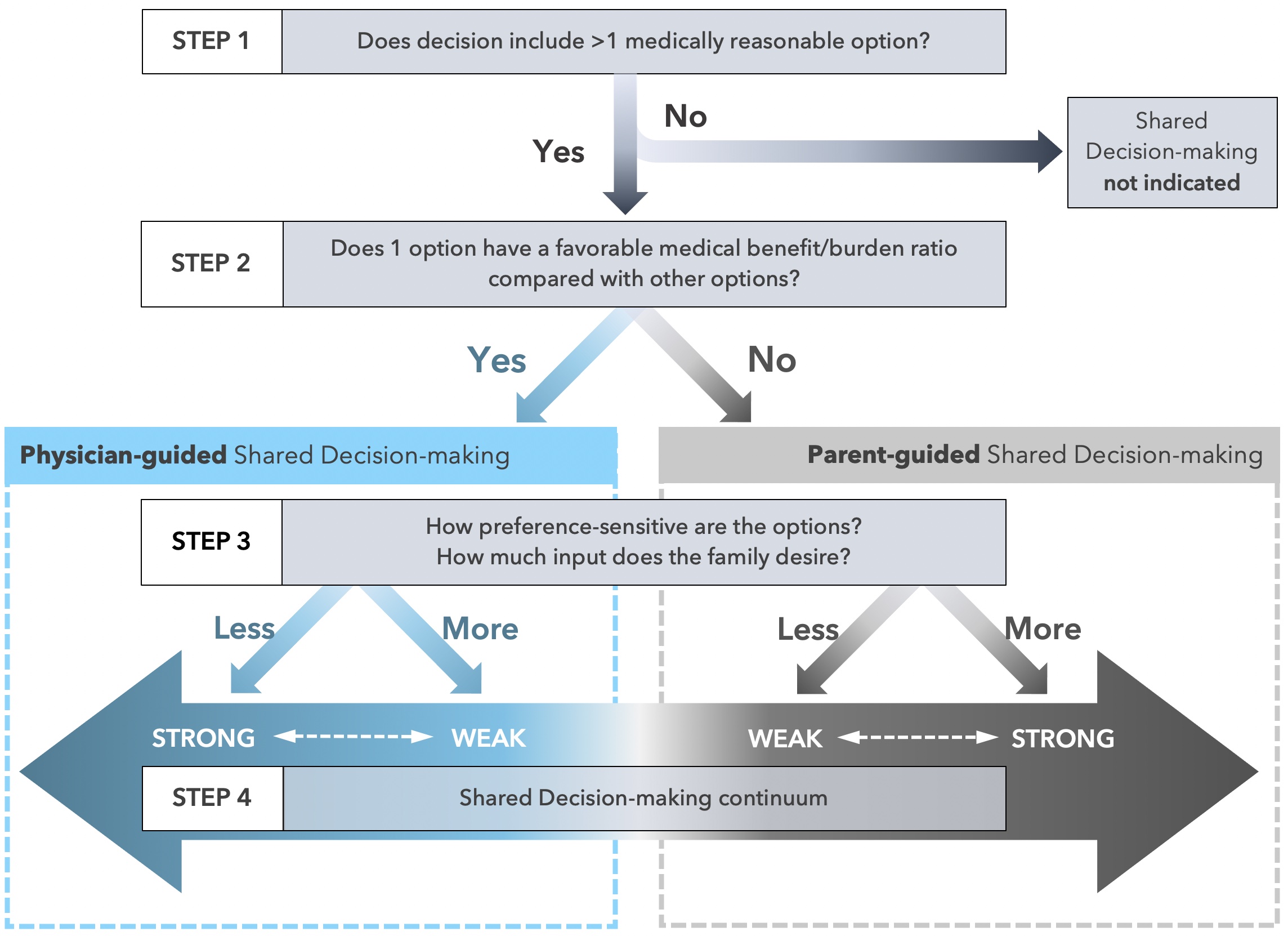

A four-step framework for shared decision making in pediatrics

In our view, the voice of ML’s family is strikingly absent in this case analysis, given the critical role it should play in the final decision that is made. Providing a framework for how to incorporate the family’s voice may be helpful for the clinical team. In addition to the Best Interest Standard and Carter & Leuthner’s framework mentioned above, we recommend a process that follows Opel’s four-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics (see Figure 1, below). [1]

Step One: is there is more than one medically reasonable option? We believe the answer is yes. Continuing ML’s current treatment is medically reasonable if there is a “reasonable expectation” she may survive to discharge and her pain can be adequately managed. [2] The alternative—withdrawing ANH—is also medically reasonable. ANH’s equivalency with other medical interventions has been firmly established in the ethics literature and adeptly described by Mr. Teti; therefore, it can similarly be withdrawn when it is incapable of meeting the goals of medical treatment. [3-7] Importantly, the decision to take ML off her ventilator was made prior to this ethics consult, and withdrawal of ANH is an ethically equivalent choice.

Step Two: does one of the medically reasonable options have a more favorable medical benefit/burden ratio? Based on Mr. Teti’s analysis, withdrawal of ANH appears to be more favorable considering the high likelihood of pain and discomfort, and low probability of ML developing the ability to appreciate the benefits of survival. When one of the medically reasonable options has a more favorable benefit-burden ratio compared to others (as in this case), physicians should assume a more directive role in shared decision making.

Step Three: what are the family’s preferences, and how should they be incorporated into the decision? This step is achieved through discussions with family members to determine how much input they would like to have in the decision. If the family expresses strong preferences, then physicians should rely more heavily on those preferences when determining the best choice. If the family feels more neutral about the options, then the physician’s own judgment (of the option that maximizes benefit over burden) can take a stronger guiding role. Without speaking to ML’s family we cannot know their true preferences; however, it is likely they would want input in the decision to continue prolonging ML’s life or allowing ML to succumb to her illness. Therefore, the decision to continue or withdraw ANH should be guided by the physician (as determined in step 2) and also integrate the preferences of the family.

Step Four: how should the appropriate approach to shared decision-making be implemented? A physician-guided shared decision that integrates family preferences should not look like offering a menu of options from which ML’s family must choose and then backing away without further guidance. Rather, a conversation with the family should include a) a description of the medically reasonable options (continuing ANH and other medical therapies, or withdrawing ANH and providing comfort-directed therapies until ML’s death) and b) their relative benefit/burden ratios, c) an opportunity for the family to articulate their values and preferences, and d) a recommendation that incorporates all of the above information. A team member who has a trusting relationship with ML’s family should lead these conversations. ML’s family may need coaching to elicit their values and preferences or apply them to the medical decision at hand; colleagues in palliative care may be particularly skilled at engaging the family in this way. ML’s family may choose either of the medically reasonable options proposed, even if the medical team disagrees or would not choose that option for their own family member. [7] Medical staff who disagree with ML’s family choice will likely need support (see below).

Beyond the decision: recommendations for human-centered care

Reaching a mutually agreed upon decision is only the first step; as ethics consultants we would provide additional recommendations to the team to promote the best care for ML, her family, and team members as they experience this tragedy together. This is in keeping with an ethic of care and the principle of beneficence. [8]

Caring for ML

The medical team can best care for ML by addressing her pain when it is evident and considering how to prevent uncomfortable sensations. They should explore if there are any positive sensory experiences for ML, such as massage, acupressure, being held or swaddled (as her condition permits), and music. They should endeavor to consider ML as a human with inherent worth and dignity rather than a problem to be solved, which can be difficult when a patient is a source of secondary traumatic stress for the staff. [9]

Promoting care between ML and her family

The entire interdisciplinary team will be essential in supporting ML’s mother, grandmothers, and father (if he wishes to be involved). Helping the family address emotional, social, and spiritual concerns will enable them to be present and supportive for ML. Incorporating their preferences as much as possible into ML’s daily care will show respect to them as individuals and the primacy of their familial relationships. Engaging her family in ML’s care and offering memory making and legacy building opportunities will also support their bonding.

Caring for the medical team

Providing medical treatment for ML could be difficult for members of her team, especially if treatments cause her pain or the individuals involved have moral distress about the treatment decisions. We advise respectfully informing members about decisions in a timely manner, and offering 1:1 staff support and moral distress forums to ensure that team members’ perspectives are heard and incorporated when possible.

While we agree with Mr. Teti’s ethical analysis, we hope that the approach we have described would further assist the clinical team in caring for ML, her family, and one another. This approach draws upon two broadly supported ethical bases that are particularly relevant in pediatrics: an ethic of care and shared decision-making. Although this situation is tragic for all involved, centering our response in caring will best protect each person’s dignity and moral sensibility.

1 Opel DJ. A 4-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018; 142: S149-156. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-0516E

2 Kon A, et al. Defining futile and potentially inappropriate interventions: a policy statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Crit Care Med. Sept 2016; 44(9): 1769-1774. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001965

3 Geppert CM, et al. Ethical Issues in artificial nutrition and hydration: A review. JPEN. 2010;34(1):79-88. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0148607109347209

4 Yarborough M. Why physicians must not give food and water to every patient. J Fam Pract. 1989; 29:683-684. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2592929/

5 Perkin R, Resnik D. The agony of agonal respiration: is the last gasp necessary? J Med Ethics. 2002 Jun; 28(3): 164-169. doi:10.1136/jme.28.3.164.

6 Casarett D, et al. Appropriate use of artificial nutrition and hydration: fundamental principles and recommendations. N Engl J Med. 2005; 335(24): 2607-11. http://www.hadassah-med.com/media/2003230/01AppropriateUseofArtificialNutritionandHydration.pdf

7 Diekema DS, Botkin JR, Committee on Bioethics. Pediatrics. 2009; 124 (2): 813-822. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-1299

8 Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. For the Patient’s Good: The Restoration of Beneficence in Health Care. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

9 Badger JM. Understanding secondary traumatic stress. Am J Nurs. Jul 2001; 101(7): 26-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11469126

Sawyer KE, MacDuffie KE. Ethics consult report commentary: withdrawal of artificial nutrition and hydration. Pediatric Ethicscope. 2019;32(1). https://pediatricethicscope.org/article/ethics-consult-report-commentary-32-1

1 Opel DJ. A 4-step framework for shared decision-making in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2018; 142: S149-156. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-0516E

2 Kon A, et al. Defining futile and potentially inappropriate interventions: a policy statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Ethics Committee. Crit Care Med. Sept 2016; 44(9): 1769-1774. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001965

3 Geppert CM, et al. Ethical Issues in artificial nutrition and hydration: A review. JPEN. 2010;34(1):79-88. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0148607109347209

4 Yarborough M. Why physicians must not give food and water to every patient. J Fam Pract. 1989; 29:683-684. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2592929/

5 Perkin R, Resnik D. The agony of agonal respiration: is the last gasp necessary? J Med Ethics. 2002 Jun; 28(3): 164-169. doi:10.1136/jme.28.3.164.

6 Casarett D, et al. Appropriate use of artificial nutrition and hydration: fundamental principles and recommendations. N Engl J Med. 2005; 335(24): 2607-11. http://www.hadassah-med.com/media/2003230/01AppropriateUseofArtificialNutritionandHydration.pdf

7 Diekema DS, Botkin JR, Committee on Bioethics. Pediatrics. 2009; 124 (2): 813-822. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2009-1299

8 Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. For the Patient’s Good: The Restoration of Beneficence in Health Care. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

9 Badger JM. Understanding secondary traumatic stress. Am J Nurs. Jul 2001; 101(7): 26-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11469126

Affiliations

Corresponding Author:

Kimberly E. Sawyer, MD

Senior Clinical Fellow / Acting Instructor

Division of Palliative Care and Bioethics

Department of Pediatrics

University of Washington School of Medicine and

Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics

Seattle Children’s

Katherine E. MacDuffie, PhD

Research Associate

University of Washington

Bioethics Fellow

Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics

Seattle Children’s

Author’s Reply to the Commentary:

I would like to thank Drs. Sawyer and MacDuffie for their thoughtful and nuanced response to this difficult case. I agree that an ethics of care is an appropriate and useful approach. I also concede ML’s family’s voice was largely absent from the report. This can be seen in the application of Opel’s four-step framework, which is particularly helpful in this case, notably “Step 3: How much input does the family want?” In this case, ML’s mother strongly felt her duty as a mother was to protect, and care for, her daughter. Unfortunately, those two goals were at war with one-another; protecting ML in the most basic sense—keeping her alive—happened at the expense of relieving her suffering—caring for what she was experiencing. The reverse was also true: relieving ML’s suffering would be to let her die. An impossible choice. Thus, like Bird in Kenzaburo Oe’s novel, A Personal Matter, [1] ML’s mother was reluctant to decide. Coping with marijuana, while understandable, made it difficult to draw out her goals and values beyond the skeletal outline of her stated desire.

Drs. Sawyer and MacDuffie are correct in that it is important to seek to better incorporate the family’s voice in ethical analyses; as clinical ethicists, our role as both participant and documenter is structurally troubling from the outset. We should not assume ourselves to be reliable reporters—this alone is sufficient reason to avoid single-ethicist consultations in favor of team-based approaches for the most complex cases (This consult was conducted by a team). Thus, if a third party feels the family’s voice is absent, I take that determination to be correct.

However, I disagree with Drs. Sawyer and MacDuffie regarding there being two medically reasonable options. This may be a factor of having seen the patient, and having discussed her prognosis with her medical team in greater detail than the report conveyed. ML’s pain was unmanageable with the strongest of opioid analgesics, and over the course of months, the palliative care team exhausted their options. ML’s obvious suffering and decline—a result of the limits of medical technology—was not offset by any clinical benefit or portent thereof. Thus, in this case we felt what was happening was therapeutic torture. [2]

Drs. Sawyer and MacDuffie’s discussion of the ethics of care is also welcome addition, as the wound care staff in particular had great difficulty with this case. Greater efforts to incorporate recommendations that addressed the impact on each person and group involved would have improved the report.

One difficulty in clinical ethics as it exists today is that different institutions have different practices and knowledge sets, and without a means to compare notes across institutions, each consult service is an island unto itself. That is the reason Pediatric Ethicscope has started this section to allow others to both share their practices and receive constructive feedback from peers at other institutions. In this way, we hope that the community of pediatric clinical ethicists can improve their consulting and reporting skills in a manner unavailable from the direct peer feedback available within any given institution.

1 Oe K. A Personal Matter. Trans. Nathan J. New York: Grove, 1969: 74-76. In: Lantos JD, Meadow WL. Neonatal Bioethics: The Moral Challenges of Medical Innovation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006: 118. doi: 10.1353/book.3245.

2 Teti SL, Ennis-Dustine K, Silber TJ. Etiology and Manifestations of Iatrogenesis in Pediatrics. AMA J Ethics. 2017 Aug 1;19(8):783-792. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.8.stas2-1708.

Replying Author:

Director, Writing Support Program

Executive Editor, HMS Bioethics Journal

Executive Editor, Pediatric Ethicscope

Center for Bioethics | Harvard Medical School

641 Huntington Avenue | Boston, MA 02115