White Space

Sharla Rent and Stephanie Kukora

White Space

ABSTRACT

In this narrative essay, a neonatologist considers “culture” and cultural competency while engaging in a global health partnership with a neonatal intensive care unit in Ethiopia. The shared medical culture between clinicians in the partnership was surprisingly unifying; experiences differed from expectations with regard to being an outsider. Ethiopian physicians, nurses, and midwives routinely encounter cultural challenges created by language barriers, an urban vs rural divide, and differences in education that impact the patient-provider relationship. Despite limitations in personnel and resources, these clinicians have devised approaches to overcome these barriers to best serve their patients. Hearing and observing how providers bridge these divides reveals important lessons for managing cultural challenges at home. Clinicians and trainees engaging in global health work should reflect on how cultural barriers experienced abroad are mirrored within their own communities, and utilize this these experiences to better inform their patient care practices.

VIEW / DOWNLOAD PDF

Pending publication of print/PDF version.

White Space

“They don’t like to take the baby out because of Evil Eye… Even it can be someone looking at the baby and it makes the baby sick. They have a fear that if they take the baby outside of the house, someone will give the baby this look, and the baby will be sick.”

—Resident in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

White Space

White Space

- In global health partnerships, we must remember that culture is not binary. It is not “us” and “them”. Beyond our national identities, we all are also part of other “cultures” – those not based on country or ethnicity, but on profession, education, or shared beliefs. Specifically, the medical community is a culture in and of itself and can be a stronger unifier than national identity.

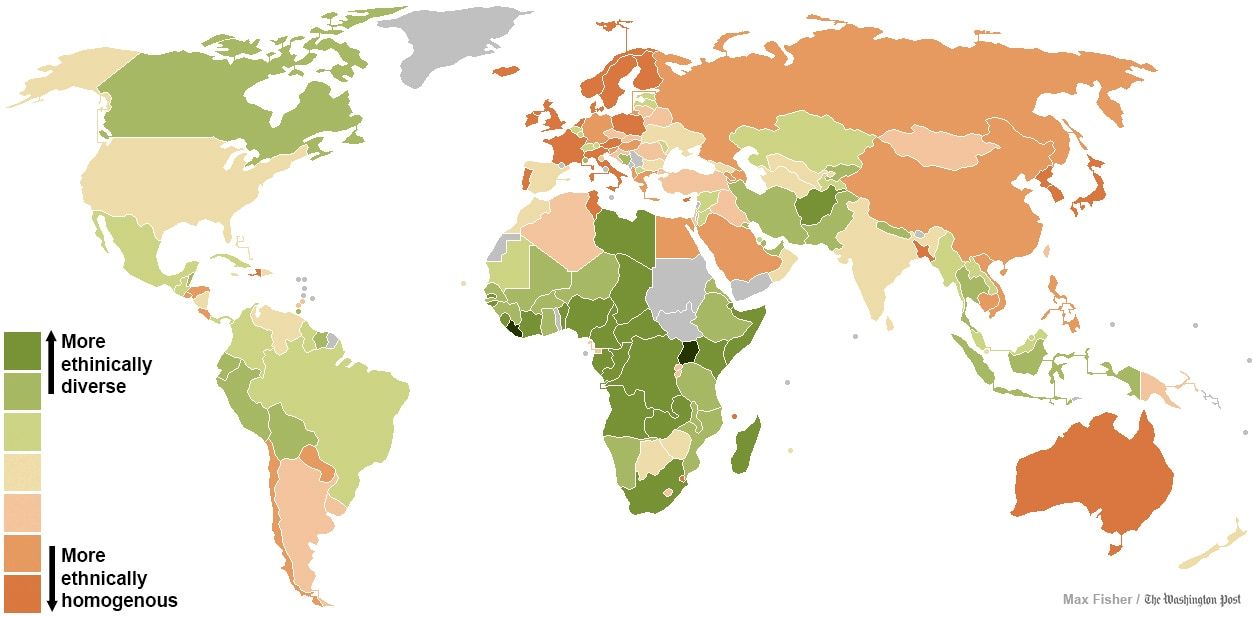

- Trainees engaging in global health work need to become cognizant of the heterogeneity that exists within the country they are traveling to and anticipate how they will work with local partners to navigate this linguistic and cultural diversity.

- Cultural barriers experienced abroad are often mirrored in our own communities and physicians should feel empowered to play an active role in bridging these cultural gaps.

White Space

IRB Approval

IRB approval for the referenced interview study, from which providers were quoted in the narrative, was obtained both from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI, USA, and from St. Paul’s Millennium Medical College in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

White Space

White Space

White Space

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

White Space

White Space

Affiliations

Sharla Rent, MD1

Stephanie Kukora, MD2,3

1. Duke University School of Medicine

Division of Neonatology

Department of Pediatrics

Durham, NC

2. University of Michigan

Division of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine

Department of Pediatrics

Ann Arbor, MI

3. Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine

University of Michigan

Correspondence

Sharla Rent, MD

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics

Division of Neonatology

Department of Pediatrics

Duke University School of Medicine

3643 N Roxboro St., Durham, NC 27704

sharla.rent@duke.edu

White Space

White Space

Endnotes

1 Ethiopia. 2007 Census. http://www.csa.gov.et/census-report/complete-report/census-2007#. Accessed May 12, 2019.

2 Ethiopia. Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/country/ET/languages. Accessed May 12, 2019.

3 Babalola, S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria–looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-43.

4 Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-34

5 Abubakari A, Agbozo F, Abiiro GA, Factors associated with optimal antenatal care use in Northern region, Ghana. Women & Health. 2018;58(8): 942-954, https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1372842

6 Lichter DT, Brown DL. Rural America in an urban society: changing spatial and social boundaries. Annual Review of Sociology. 2011;37:565–592. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150208.