The Conflicting Principles Underlying the Drug Shortages Crisis

Stowe Locke Teti

ABSTRACT

The issue of drug shortages can be framed as those who wish to ensure drug availability in virtue of dedication to the patients’ interests, on one hand, and those who herald economic responsibilities, on the other. The former group maintains this is an ethical issue; the later contends the economic realities cannot be ignored. In situations where one group insists an issue is “ethical” but the other disagrees, an impasse is formed; if two parties cannot agree on the premises of an issue, no debate is even possible. In Philosophy, the study of ethics is a subset of the study of value in general. Whereas ethical values are often characterized in terms of “right” or “wrong,” there are other types of values, often expressed in terms of “good” or “bad.” These are not ethical values, but values of this more general type. The study of this type of value is classified in philosophy as value theory, or Axiology. The purpose of this article is to expand from an ethical analysis of the issue of drug shortages and drug pricing to include, pari passu, values in this larger sense. An axiological examination can provide an overview of both ethical and other values, a lingua franca, of sorts, from which to fruitfully draw conclusions about the issue of drug shortages as a societal ill.

Overview of the Drug Shortages Problem

Everyone wants sick patients to have access to the medications that can help them; divisions form between two groups, roughly according to the specific principle, or principles, each group deems paramount. The issue of drug shortages can be framed as those who wish to ensure drug availability in virtue of dedication to the patients’ interests, on one hand, and those who herald economic responsibilities, on the other. The former group maintains this is an ethical issue; the later contends the economic realities cannot be ignored. In situations where one group insists an issue is “ethical” but the other disagrees, an impasse is formed; if two parties cannot agree on the premises of an issue, no argument is even possible. To wit, in a 2013 article titled, “Why drug shortages are an ethical issue”, authors Lipworth and Kerridge outline the causes of drug shortages, but conclude:

“It is an open question whether these behaviors represent unethical conduct or are simply “rational” behavior in a market system.” [1]

In Philosophy, the study of ethics is a subset of the study of value in general. Whereas ethical values are often characterized in terms of “right” or “wrong,” the characterization of one’s work, interests, and politics are often expressed as “good” or “bad.” These examples are not ethical values, but values of this more general type. [2] The study of this type of value is classified in philosophy as value theory, or Axiology. Axiology includes the study of ethics, the study of aesthetics, and this general type of value as its subject matter. [3] All ethical problems are in that sense axiological problems, but the reverse is not true. In considering the issue of drug shortages, or drug pricing, sometimes we may think we are speaking a different language than pharmaceutical industry representatives, and the pharmaceutical industry likely feels that way when talking with the FDA; in an axiological sense, we are speaking different languages. The purpose of this article is to expand from ethical analysis to include, pari passu, values in this larger sense. An axiological examination can provide an overview of both ethical and other values, a lingua franca, of sorts, from which to fruitfully draw conclusions about the issue of drug shortages as a societal ill. [1]

But it may be that different sets of values are incommensurable; there may not exist a way to develop criteria that can be used to critically assess these varying values. In aesthetics, most would probably agree that we can’t compare what one person appreciates in a painting with different things another appreciates, and say one is a “better” way to appreciate the art. [4] A fair enough criticism, but if two different value systems share common elements, we can take the values common to both, such as, for example, being consistent, telling the truth, or obeying the law, and examine the conflict in light of those shared criteria. The result would be, if not indicative of a definitive course of action, indicative of improvements to be made. In the most general sense, drug shortages are caused, ultimately, by our societal values; the choices we make about how we want our health care delivered, the power we vest in our government, and the economic system we endorse. [5,6] One commentator noted, “Our value-laden social, political and economic choices are obviously contributing to drug shortages.” [1]

This article proceeds as follows. First, an overview of the history of drug shortages and their effects will set up the values in conflict. That is followed by teasing out the reason drug shortages are inherently linked to drug prices. That leads into the question of motivations, the “why” and “how” of pharmaceutical industry decision-making, which will be explored with an eye to historical context. With that in hand, two examples will be considered, both of which will be shown to be proxies for industry behavior and social expectations writ large. All the parts will then be in place to examine some general values common to both value systems, from which conclusions valid from both perspectives may be drawn.

Drug Shortages History and Breadth

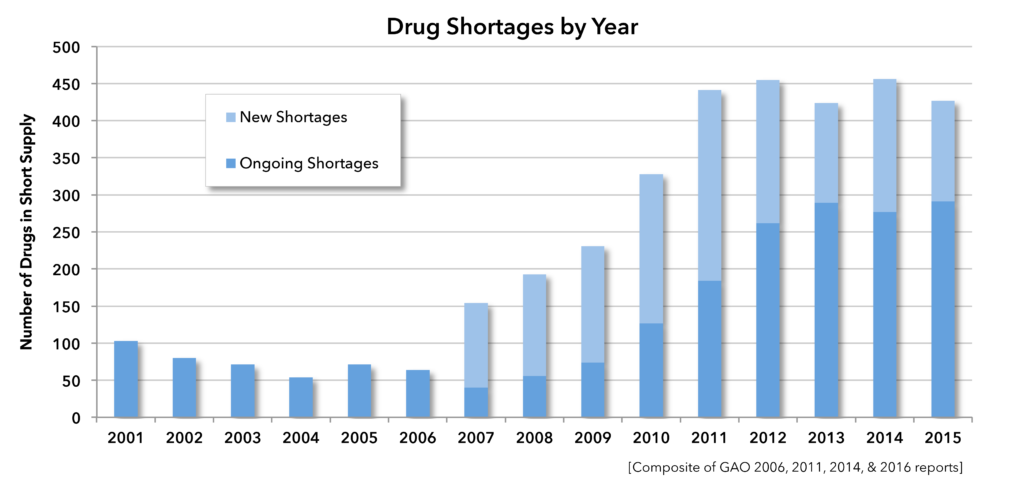

Drug shortages began escalating in 2005. [7] By 2007, the FDA listed 154 drugs in short supply; that number reached an apex of 456 by 2012. At the beginning of 2016, more than 300 drugs were in short supply [8] Because some drug shortages persist for multiple years, the total number of drugs in short supply continues to escalate, [9] as shown in Figure 1. This finding is born out in practice as shown by the research of Metzger et al., as cited by Yoram Unguru in this issue of Pediatric Ethicscope, and recently by a 2016 survey conducted by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The AAP study found that over 72% of the study’s 365 respondents, representing both general pediatrics and seventeen distinct pediatric subspecialties, experienced increased drug shortages over the past two years. [10] These shortages can leave even the most prepared hospitals unequipped to treat their patients should such a need arise. This and other problems resulting from drug shortages have been highlighted by Dr. Unguru, his colleagues, and numerous other physicians who have encountered this problem and are working on behalf of their patients to resolve it. [11,12,13] But even a cursory look at the titles of any of the numerous news stories that have been written over the years to alert the public about drug shortages reveals startling charges of unethical conduct at one extreme, and capitalist resoluteness at the other. [9,14,15,16] Research and academic works fare better, but it would be inaccurate to say the issue is not polarized. [17]

Figure 1. Drug shortages by year.

The overall costs to society of shortages are difficult to quantify; the values involved include time, money, professionalism, and health, to name a few. Hospital pharmacists must spend time searching for drugs (described by Dr. Jeffery Dome in this issue), physicians must spend time developing and implementing alternative treatment plans, patient stays can be longer, or involve more other hospital services as less effective therapies are employed, with potentially inferior outcomes. Patients, physicians, and hospitals experience delays in many drugs that are not considered or reported as shortages. A 2011 study done by the healthcare provider alliance Premier, found that more than 400 generic drugs were backordered 5 or more days in 2010 [18] requiring staff to attempt to effect procurement at least twice in each instance. Their other findings are staggering:

• 89% experienced a drug shortage that may have affected patient care, and that occurred more than six times for over half of those.

• 80% experienced a drug shortage that resulted in a delay or cancellation of a therapy or intervention, and that occurred more than six times for 30% of them.

A study by McLaughlin et al., found 40% of the 193 pharmacy directors who participated reported between one and five adverse events “probably or possibly,” associated with drug shortages at their institution. [19]

All these issues result in manifold increases in the cost of medical care. According to a 2013-2014 study done by Premier, searching for alternative treatments costs hospitals at least $230 million more per year than they would otherwise spend in the wake of the drug shortage epidemic, [20] down from $415 million in 2010. [21] The financial cost of the drugs themselves is staggering, [22] growing several points in excess of the growth of healthcare expenditures overall. [23] If a brand drug must be substituted for a generic many times the typical cost will be incurred; if brand drugs aren’t available, resorting to the gray market to obtain a lifesaving therapy can visit as much as a 4,500% markup (650% average) upon the patient, hospital, and health system. [21] The human costs are no less staggering; numerous deaths have been linked to the effects of shortages according to recent reporting. [15,16]

While one may assess such findings in generalized terms, which is appropriate to policymaking, these statistics are comprised of many thousands, or millions, of individual cases, cases in which physicians’ efforts to treat their patients may be effectively stymied by an inability to employ what is often their best, or only, resource: pharmaceuticals. And the human costs? In extreme cases it was put succinctly by Deborah Bankera in 2011, referring to the effects of the then-current cytarabine shortage:

“With this drug they can be cured and without this drug too many of them will certainly die. That’s the simplest way to put it. The disease progresses so rapidly that untreated patients can sadly die within days. There is no time for delay and no certainty of a good outcome if you can’t get a full dose.” [16]

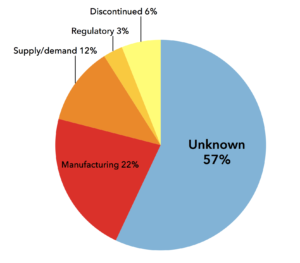

It is therefore a natural question to ask, “Why is this happening? What processes are at work such that this is the result, and what are the values at work?” In the charts put out by the GAO and FDA, the categories listed as causes of drug shortages are: Supply/demand, Manufacturing, Regulatory, Discontinued, and Unknown (See Figure 2). [24] At 57%, “Unknown” is the largest category, and while numerous reports indicate business decisions are perhaps the leading cause of shortages, [25,7] that most salient fact is difficult to locate at all in official reports put out by the governmental bodies charged with oversight of the pharmaceutical industryb, [26,27] perhaps because attribution to human decisions invites value-based judgments.

Figure 2. FDA and GAO reported reasons for drug shortages.

In response, it has been argued the pharmaceutical industry is a large, labyrinthine even, enterprise that defies generalization, subject to demands of continuous innovation, and incorporates high risks. [2537-52] But those facts alone do not foreclose all efforts to understand the dynamics of the problem. There is information from which at least preliminary conclusions may be drawn, [25] insights that perhaps can eventually serve not only the patient populations affected, but also the public interest at large. However, a purely ethical framework seems to lead to a polarization of positions, with neither side willing to acknowledge the legitimacy of the values held by the other. [28] One central argument that will emerge is an empirical finding: the issue of drug shortages is inexorably tied up with the problem of drug pricing, for as it will be shown, the later induces the former. Underlying this dynamic is a conflict of ends; physicians uphold a fiduciary duty to their patients, whereas the pharmaceutical industry’s fiduciary responsibility is to its stockholders. [29]c

The Industry Develops: Roots, Innovation and Blockbusters

Yoram Unguru points out recent reporting on the “availability of generic drugs, and chemotherapeutics in particular, is directly linked to decisions by manufacturers that either delay or prevent these drugs from becoming accessible.”[11] Many contend such tactics have a financial basis, a sentiment the industry challenges. Complicating matters, drug companies do not make their internal decision-making processes available; Angell quotes New York Times reporter Robert Pear, who in 2001 contended, “The basic problem is that all pharmaceutical costs, including research, are in a black box, hidden from view. There is no transparency.” [30] While the actual costs of drug development are unavailable for public scrutiny, the public is invited to presume such costs are extraordinary, thus justifying drug pricing. [25,31] However, no consensus of faith exists, nor, despite being an empirical matter, does governing corporate law require any divulgence of facts. As a result, an impasse exists; contentions of fact, lacking an undergirding trust, are assumed to be false. However, one can surmise what is going on inside “black box” and deduce the reasoning by looking at the macro-scale industry behavior, economic outcomes, and the resulting industry trends; one can look at accepted business practices and applicable laws. One can also use the tools of ethical analysis, from the perspective of industry.

In narrative ethics, the patient’s story is considered as a means to understand her values and interests, thereby allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the case through an understanding of the motivations, the stories behind those motivations. [32] What follows is application of that process to the pharmaceutical industry, to explore the values and interests concomitant with drug shortages; again not as an ethical critique per se, but as an axiological analysis.

A historical perspective aids this inquiry. In the mid to late 1800’s, drug companies such as Merck and Eli Lilly were what are commonly now referred to as “snake oil salesmen,” selling products containing quinine, morphine, cocaine, and heroin. [33] But like the regulations governing biomedical research, which have aptly been described as having been “born in scandal,” [34] it took the deaths of thousands of people, and countless infants who were unknowingly given opiates, for Congress to act; the 1906 Food and Drug Act required listing ingredients of medications on product labels, and was the first step towards today’s regulatory schema. [35] The Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 required toxicity testing, establishing the beginning of double blind studies, much to the drug industry’s chagrin. [36] The introduction of Penicillin marked the turning point in the industry’s public image, as Syphilis rates in New York City were cut by 75% between 1943 and 1953. [36] The intervening of World War II, and penicillin’s role in life-saving had a profound effect; Paul Starr notes, “During World War II, the research effort that produced radar, the atom bomb, and penicillin persuaded even the skeptical that support of science was vital to national security.” [37] Whereas between 1900 and 1940, the primary sources of medical and pharmaceutical research were private, with groups like the National Academy of Sciences opposing any large-scale Federal funding, [37336–339] the NIH’s budget, $180,000 in 1945, swelled to $874 million in 1970. [36]

The importance of the American system of medical care delivery had a profound effect on our conceptions of the ethics of drug shortages. During the ascent of modern medicine, a page of Time magazine was devoted each week to modern advances and “wonder drugs.” This was evidence life was getting better, [37336] as Henry R. Luce of Fortune Magazine called it “the American century,” and Fortune’s editors referred to capitalism’s “permanent revolution.” [37336]

However, the purchase of drugs was uncoupled from the consumer relying on them in two ways: only physicians could access the most potent ones, and insurance companies were handed the bills. [38] According to Philip Hilts, author of Protecting America’s Health: The FDA, Business, and One Hundred Years of Regulation, pharmaceutical industry profits reached 19% after taxes in 1957, and “were unlike anything seen in the history of sales.” [38] At the same time, the decoupling of payment from consumer, and growing success in the industry, left, “all concerned consuming the novel meds–the new American birthright–in ever increasing quantities.” [3639,37 338]

So, while penicillin recast the industry as purveyors of social goods, [36] drug companies are, and always have been, in the business of making money, like a bank or technology company. Unlike physicians who see their principal duty is to their patient’s best interestsd, Big Pharma sees its responsibility is to its stockholders, who could invest their money elsewhere. While physicians developed a profession centered on principles society endorsed, Big Pharma contended with what some see as an arrogation–that an obligation to patients exists in virtue of the product they produce.

The growing power of the industry, represented by the tremendous growth of the NIH in the postwar years, had both formative and definitive effects on both behavior and policy. Marcia Angell, former NEJM editor, points out in The Truth about Drug Companies, that between 1960 and 1980, prescription drug prices remained a relatively static percentage of GDP, but from 1980 to 2000, that percentage tripled. [255] What accounts for the remarkable 9.9% annual growth in drug spending for that period? According to Angell, Reagan Administration policies “Let the good times roll” [256] through legislative efforts aimed at “technology transfer”, the transfer of basic research into marketable products.

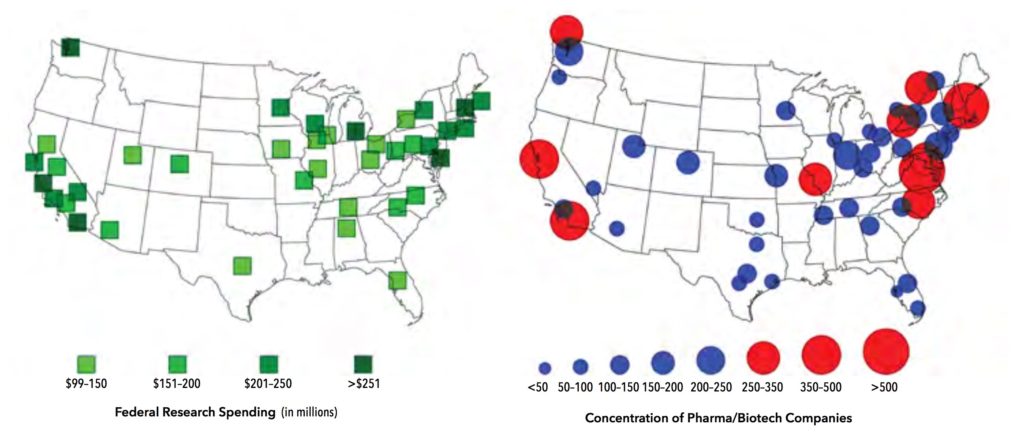

The story of one such effort begins with Senator Birch Bayh (D-Indiana) and Robert Doyle (R-Kansas), who sponsored the Birch–Doyle Act. [39] The Birch–Doyle Act enabled businesses and universities to patent discoveries funded with public research dollars, such as NIH-funded research, and then to grant exclusive licenses to drug companies. As a result, drug companies no longer needed to rely on their own research. Even if they had, the opportunity to access the work being done at universities across the country would have been irrational to pass up. A comparison of the two accompanying maps of the United States illustrates the results (Figure 3). On the left is a map showing the allocation of government funding to research universities. On the right is a map showing the locations and concentrations of biotech and pharmaceutical companies. Birch-Doyle had a significant impact on the creation of the Biotech sector of the U.S. economy (although the trend was already underway prior to 1980) by promoting the transfer of basic research into practical products. [40].

Figure 3. Left: Federal research spending at institutions of higher education; Right: Location of biotech corporations headquarters and main offices.

It is apparent from both the data and the geographic locations of these companies that federal funding is a principal, if not primary, source of the research that industry draws from in the development of drug products, but that is not necessarily problematic; their products could still broadly serve patients needs. And while one can understand the desire to mitigate the risks of spending money on basic research, there is a point at which risk aversion has a deleterious effect on advances in patient care.

This point represents another axiological conflict between the industry’s valuation of its own business security and the patient’s/physician’s/hospital’s (and perhaps the public’s) valuation of the patient affected as a social ill. [29] However, empirical evidence suggests that risk aversion in the pharmaceutical industry is significantly greater than Pharma marketing purports. [2552] Angell points out that “me too” drugs comprise a significant proportion of the drugs being produced. In the period from 1998 to 2002, of the 415 drugs approved by the FDA, only 14% were innovations. 9% were old drugs modified in such a way as to be patentable as “new,” leaving 77% that were, according to the FDA, no better than existing drugs on the market. [2574-75] In 2013, of the $300 billion in sales reported by the the 13 Big Pharma companies, $123 billion no longer had patent protection, meaning the pharmaceutical industry sold more generics than the generic industry itself, which returned $70 billion that year, and that was an 18-year high for the industry. [41]

Angell argues this occurs because of a “crucial defect” in the law; new drugs do not need to show they are superior to existing drugs, only that they are effective compared to placebo. The central claim those who advocate “comparative effectiveness” approaches to drug studies is this: shouldn’t studies be done comparing the newly proposed drug to those it is intended to supplant? In practice this is not often done, [2574-78,42] and the reason cited is that showing any difference would be difficult without resorting to large (and therefore expensive) studies; it is difficult enough to show effectiveness compared to a placebo. According to Robert Temple, MD, Deputy Center Director for Clinical Science at the FDA:

The main difficulty with doing comparative studies is that the effects of most drugs, while valuable, are not very large, so that even showing a difference between the drug and no treatment (a placebo treatment) is not easy. [42]

However, it could be argued that even, say, a 10% improvement is significant for the patients whose conditions are ameliorated by the drugs the industry does produce. If the industry’s efforts only yield that number, who would criticize their profiting on “me-too” drugs–perhaps those support the development of innovative drugs; after all theirs is not an easy task. Gleevec, (imatinib mesylate) for example, was a true innovation–a drug that treats chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a rare condition that was prior to its introduction, always fatal. Gleevec, a Novartis product, was used in broad marketing efforts as “the poster child for drug company innovation.” [2562]

However, the molecule used in Gleevec was based on the “Philadelphia chromosome,” so named for the University of Pennsylvania, where researchers Peter Nowell and David Hungerford discovered it in 1960. [43] The Philadelphia chromosome carries a gene involved in the production of bcr-abl tyrosine kinase, an enzyme that causes white blood cells to become cancerous because the kinase remains permanently active, driving cell division. In 1988 an industry researcher at Ciba-Geigy, Nick Lydon, approached Brian Druker, a researcher at Oregon Health and Sciences University, about developing a drug to block particular enzymes thought to be causal elements in some cancers. Druker suggested CML, and investigated a number of compounds Lydon had developed based on the Philadelphia chromosome. [2563] Druker found one, STI571, which inhibited the CML cell action; in fact, it killed all of the CML cells in petri dish. Ciba-Geigy patented the compound in 1993, and by 1995, STI571 was ready for clinical development. In 1996, a merger occurred creating, Novartis and bringing a stop to development of STI571. Lydon left the company, but Druker pressed the new management to continue the work. They resisted. [44] Druker, Lydon, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center researcher Charles Sawyers had found imatinib mesylate successfully suppressed the growth of cancer cells while not affecting healthy cells, a highly unusual finding in cancer research, where chemotherapeutics generally work by targeting cell division in general. [45,46] With Novartis management not interested, Druker persisted. With limited support, he was able to begin Phase 1 trials. He demonstrated incredible results in 1999; once patients were given effective doses, Druker got a 100% response rate to the drug. [44] Angell argues, “Most of Novartis’s R&D investment in Gleevec was made years after there was good scientific evidence to suggest that the drug would be useful.” [2566]

That may be true, but Novartis would have undoubtedly developed the drug if they knew what would result. Given that 9 out of 10 drugs that reach clinical trials don’t make it to market, [47] and by definition those ten have “good scientific evidence” supporting their development, the chance was only one in ten that imatinib mesylate would be a “hit.” Rather than being a function of rationality or risk, the difference in what Angell would presumably have done, and what Novartis did, was likely one of value; a physician and former editor of NEJM has a different relation to the imatinib mesylate findings than a business insider or economist. We know this intuitively, and take it into account when speaking with people, expecting people of different backgrounds, who have made different choices in their lives, to have different opinions on matters of value, and thus different assessments of risk. It is clear this is an axiological difference, but it is not clear it is an ethical one. Even the very rich could quickly go broke trying to fund ten out of ten compounds with “good scientific evidence” of potential benefit.

Looking to the more recent past, after adjustments for inflation, spending tripled again on prescription drugs between 1997 and 2007. [48] During those two decades, “blockbuster” drugs, those selling in excess of $1 billion in the United States, increased from six in 1997 to 52 in 2006. As a proportion of all sales, that represents an increase from 12% to nearly 50% of all drug sales. [48] But in order for sales of “blockbuster” drugs to increase, one of two things needed to happen. One, drug companies could add production capacity, or two; they could reallocate the production capacity they already possess. In either event, production of less profitable drugs decreases. In the former case, decreases occur as a percentage of total drugs being produced; in the latter, decreases occur relative to what was produced previously. Businesses exist to make a profit, and a CEO who did not reallocate resources so as to produce the greatest return for her stockholders would not be meeting her fiduciary obligation to them. [29] This basic economic reality is the missing component in the “Causes of Drug Shortages” charts. To be fair, some charts by other organizations include “business decision” as a category, but generally list its contribution to be less than 10%. As investment banker Lawrence Perkins stated in a Western Journal of Medicine commentary, it should not be any surprise that drug company decisions are based purely on making money:

“Regardless of what a company is selling, they are in the business of making money and satisfying their fiduciary duties…Chandrasoma argues that pharmaceutical companies have an obligation to society to produce medicines that address all afflictions and to avoid discriminating against a particular disease or condition. But pharmaceutical companies have to discriminate because, like other commercial enterprises, every day they must answer the following question: can we afford this venture? This decision must be based purely on sales and costs.” [29]

Every business must cover its expenses and make a profit if it is to stay in business. The ‘affordability’ of producing pharmaceuticals is an empirical question; like all businesses, the costs Perkins referred to must be known to be calculated, and while those facts are closely-guarded industry secrets, [2537-51] the facts we do have in our possession, setting aside ethical concerns for the moment, indicate the characterization, “can we afford this venture?” is disingenuous. We are not talking about financial solvency; as Angell points out, the pharmaceutical industry is tremendously profitable. In 2015-16, Pharma, Biotech and Life Sciences returned consistent net margins of between 19.5% and 20%, [49] tied with the highest performer, banking. The pharmaceutical industry has been returning profit margins well above most other economic sectors for many years. [2574-75] By way of comparison, oil and gas companies, and automakers, returned profits in the single digits. [50] The extent of Big Pharma profits cannot be overestimated; in 2013, Pfizer’s profit margin was 42%. [51]

Whether it was the shortage of childhood vaccines in 2000 that followed the 1994 CDC market cap on inflated prices, or the chemotherapeutic shortages discussed in this issue of Pediatric Ethicscope, the underlying issue is the competing fiduciary duties at work. As Mark Goldberger, who coordinated the FDA’s response to the vaccine shortage in 2001, stated:

“We have to give approval for companies to make the drugs, but companies can leave the marketplace anytime they wish.” [52]

That being said, there are value-based concerns within the set of values industry accepts: capitalism. Selling anything and everything, regardless of its impact on the people who use it, is considered neither good business, nor legal. The 1906 Food and Drug Act requiring labels, the 1938 Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics Act requiring toxicity testing, and a range of modern laws have improved the industry’s ability to remain competitive and acceptable in modern society. Being truthful about one’s products is also a capitalist value, and importantly, competition is a capitalist value. However, there are industry actions that do not appear to meet either values expected by capitalist society at-large, or the more demanding expectations of ethical conduct.

Drug Shortages: The Case of Mechlorethamine

Mechlorethamine is perhaps the clearest example of a lifesaving medication, a stalwart of pediatric cancer treatment, which the pharmaceutical industry manipulated to maximize financial returns at the direct and predictable cost of patient’s well being. It is a good example because it has been in use for many decades, and thus no current company can claim the need to recoup R&D expenses. It is also a good example because its story involves several pharmaceutical companies over a period of years, and thus exemplifies a common practice. As such, it seems reasonable to take this example as bearing the industry’s imprimatur.

In 2006, Mustargen was produced by Merck Pharmaceuticals. According to reporting at the time, Merck wanted to raise the price, but the company’s highly visible public image made such a move undesirable. [7]. Merck sold it to Ovation Pharmaceuticals, a small company, thus without such concerns. Ovation raised Mustargen prices 1000%. Merck continued to manufacture the drug; Ovation merely purchased and resold the finished product. [7] In March of 2009, the FTC approved the purchase of Ovation by European giant Lundbeck for $900 million. In a March 19 press release, Lundbeck stated:

“Today’s announcement will not affect or interfere with any product availability or support for any of the products that Ovation currently has on the market.” [53]

By early September 2010, the FDA had listed Mustargen as in short supply. Nearly two years later, on November 5 2012, the FDA relisted the shortage as “resolved.” At that time, Lundbeck made the following public statement:

“[We are] pleased to announce Mustargen is once again available in the U.S…We’ve worked closely with the FDA and invested significant resources [in] a state-of-the-art facility that will help enable a consistent, reliable, long-term source of product…Thank you for your patience…We are very pleased to once again be able to make this important therapy available to your patients.” [54]

But the sentiment of that statement was short lived. On December 14 of that year, just 39 days after Lundbeck praised itself for creating a “consistent, reliable, long-term source of product,” [54] the companies sold Mustargen to Recordati Rare Diseases; another company with a history of employing purchase/price-hike tactics. [55] Since Lundbeck’s reference to manufacturing capabilities is instructive to investigate. As has been cited previously, the causes for drug shortages have been described as “complex.” In fact, the GAO’s November 2011 Drug Shortages findings, after separating external factors such as raw material shortages, divided the causes of drug shortages into the following three categories:

- Temporary manufacturing shutdown to upgrade an entire facility.

- Temporary manufacturing suspension of a particular drug to investigate or resolve a manufacturing problem.

- Unspecified manufacturing delays. [56]

As noted, visibly absent is any attribution of drug shortages to business decisions. However, it is notable that the reasons cited all relate to the means by which sales of blockbuster drugs can increase; all relate to capacities of production. This is, in essence, correct, because the FDA gives permission for a particular manufacturing line to produce a particular drug, so that product production cannot be shifted around to accommodate shortages without changes to the FDA production specifications. These reasons, and those offered by Lundbeck, are written in the language of production, and while they are intended for use by patients, that is not the mindset of those who show up for work at Lundbeck every day. They are, as Lawrence Perkins argued, there to make money, not to save or better lives. A 2012 Harvard Law School analysis of drug shortages concluded:

“Although it is tempting to view manufacturing problems as an independent cause of shortages, the more likely story is that manufacturing problems are just a consequence of another underlying cause.” [57]

And in the case of Lundbeck and Mustargen, a review of Lundbeck’s financial reports reveals a statement discordant with the sentiment expressed just over a month prior, but consistent with their values and duties to their stockholders:

“…Some of our products are maturing, and we are addressing this challenge by focusing on our pipeline, partnerships and new product launches… Our new products generated total revenue of DKK 2,141 million, which is more than we lost on the patent expiration of Lexapro in the US…” [58]

“Maturing,” is industry speak for heading “out of patent,” a condition also known as “loss of exclusivity” (LOE). In essence, this means the company’s product is at risk of facing competition in the marketplace. It is notable that the free market is the very thing industry defenders point to when arguing government regulation is not necessary; free markets are, according to this line of argument, “self-regulating.” [17, 59] But the evidence shows that two things pharmaceutical companies eschew are risk and competition.

Being out of patent is a decidedly undesirable state of affairs for a pharmaceutical company. Consider: analysts predicted that when Pfizer’s cholesterol fighter Lipitor came out of patent in 2010, the company’s revenue stream would be slashed by 25% by 2015. In few industries are there businesses that rely on a single product for 25% of its revenue. Financial reporting of Lundbeck and other companies show an increasing trend towards focusing on new drugs. [16] Unless manufacturing facilities are expanded to do this, something has to give, thus creating “orphan” drugs and drug shortages. [60]

Pointedly, sterile injectables, touted as difficult to manufacture, are rarely unavailable in brand formulations according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which also found the same relationship holds for even new, never before manufactured drugs if they enjoy protection by patent or other market exclusivity arrangement. [61]. Moreover, the Harvard Law School analysis noted the common sense response to ‘manufacturing issues’ as causally determinant:

Most manufacturing problems would be avoidable if a firm simply invested adequate resources to improving its facilities and procedures. [57]

Concluding:

“There is some evidence of the profit-dependence of manufacturing prowess.” [57]

However, whether difficult to manufacture or not, sterile injectables do suffer one logistical hurdle that seems to significantly affect their availability in generic form; they are “just in time” drugs, meaning they must be manufactured and used quickly because they have an inherently short shelf life. [5721-22,62] Inability to store means a manufacturer must guess at a production volume, knowing surplus will go unused, and thus unremunerated. Finally, drugs that are short in one market are often available elsewhere. [63] And before you consider travelling to obtain treatment, some locations require residency to even purchase the drug.

Drug Shortages: The case of Turing Pharmaceuticals

The issue of drug shortages cannot be evaluated without evaluating the business calculations that comprise industry strategies. Turing Pharmaceuticals is a case in point, for while extreme, it exemplifies a growing trend among many pharmaceutical companies in which the public interest is completely subverted for the pursuit of profit at all costs. Consider former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals Martin Shkreli, who infamously increased the price of a single pill of the 62-year-old drug pyrimethamine (Daraprim) from $13.50 to $750 in 2015, a more than 5,000% increase. [64]

This captured the attention of Congress, and preceding congressional hearings ranking Democrat on the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Rep. Elijah Cummings (MD) summarized key findings in two released memos. Among the findings drawn from 250,000 pages of documents from Turing Pharmaceuticals was evidence of a business model built around buying particular medications for which there were no alternatives and hiking the prices sky high. [65,66,67] In a separate report released by Senators Collins (R–ME) and McCaskill (D– MO) found four companies, Turing, Retrophin, Rodelis, and Valeant, all engaging in a business model that enabled them to identify and acquire off-patent sole-source drugs over which they could exercise de facto monopoly pricing power, and then impose and protect astronomical price increases. [65] The business model consists of five central elements:

- Sole-Source. The company acquired a sole-source drug, for which there was only one manufacturer, and therefore faces no immediate competition, maintaining monopoly power over its pricing.

- Gold Standard. The company ensured the drug was considered the gold standard—the best drug available for the condition it treats, ensuring that physicians would continue to prescribe the drug, even if the price increased.

- Small Market. The company selected a drug that served a small market, which were not attractive to competitors and which had dependent patient populations that were too small to organize effective opposition, giving the companies more latitude on pricing.

- Closed Distribution. The company controlled access to the drug through a closed distribution system or specialty pharmacy where a drug could not be obtained through normal channels, or the company used another means to make it difficult for competitors to enter the market.

- Price Gouging. Lastly, the company engaged in price gouging, maximizing profits by jacking up prices as high as possible. All of the drugs investigated had been off-patent for decades, and none of the four companies had invested a penny in research and development to create or to significantly improve the drugs. Further, the Committee found that the companies faced no meaningful increases in production or distribution costs.

Manufacturer consolidation, drug shortages, and monopolistic tactics that limit competition create fertile ground for predatory pricing. [68] This business model leverages two key factors: first, since the drugs were not invented by the company there would be no costs associated with R&D, and second, because the target drugs were needed by patients to survive, and no alternative therapies of clinical equipoise existed, demand would be inelastic. [66] Therefore, price elasticity, which is almost always negative, would remain at approximately one; as prices rise, demand does not decline, as it typically would when governed by the laws of supply and demand. Price hikes could be steep and made with impunity; revenue, rather than decreasing as demand drops, would simply increase as well. As the deal for Daraprim was closing in May of 2015, Shkreli wrote in an email to the chairman of the board:

“Very good. Nice work as usual…$1bn here we come.” [69]

Shkreli also wrote in August of that year that the price hike would bring in $375 million per year for three years, “almost all of it profit.” [69] Documents from Turing Pharmaceuticals show skyrocketing drug prices were part of the plan from conception. Turing Pharmaceuticals anticipated that HIV patients, who are particularly in need of protection from infection, could be, the company opined, a problem by virtue of their strong and public advocacy. Turing’s plan was to mollify backlash through misdirection and obfuscation. Shkreli pointed to coupons, patient-assistance programs, and discounts, as evidence the company was committed to making sure the medication was available to the patients who needed it; meanwhile they increased the prices orders of magnitude and hid the real cost from the public–as had been the plan from the beginning. While patients did not pay full-price for the drug, reporting by the Chicago Tribune revealed some patients still ended up with $6,000 copays, and at least one patient having a $16,830 payment. [69]

However, while this trend is expanding in the industry, some groups are fighting back. Bloomberg recently reported on the pharmaceutical lobbying group Biotechnology Innovation Organization’s (BIO) new “Costs in Context” initiative, which is directed specifically at distancing its members from the likes of Turing. It points to PhRMA infographics that highlight facts that cast the industry in a positive light, but those facts are still highly selective. [70,71]

Axiological Assessments and Ethics

These are but a couple examples of a troubling trend. As New York Times reporter Alex Berenson noted in 2006:

“people who analyze drug pricing say they see the Mustargen situation as emblematic of an industry trend of basing drug prices on something other than the underlying costs. After years of defending high prices as necessary to cover the cost of research or production, industry executives increasingly point to the intrinsic value of their medicines as justification for prices.” [7]

Berenson is observing an axiological shift within the pharmaceutical industry, or at least as a marketing effort, and one borne out in fact: Premier found the highest marked-up drugs were ones needed to treat critically ill patients. [21] This strategy raises overtly ethical concerns less easy to defend on economic the grounds. The observation posits a change in how medications should be evaluated in determining their worth–rather than be evaluated by the traditional costs of production, lifesaving drugs should be priced according to their “intrinsic value.” In this setting, the intrinsic value of a drug can mean only one thing, its value to the patient who needs it to survive. Even the Bloomberg reporting referred to above refers to the “profound value” to patients. [70] Seeing families of very ill children every day, there is no doubt that most or all of them would give everything they have to save the life of their child; many do precisely that. So let us tentatively accept the intrinsic value of many of these drugs can end up in some sense equaling the lives they save–that is the opportunity cost of going without them–is this the correct way to assess their economic value?

Two lines of argument address the notion of drug value as an axiological question. The first is a categorical argument. In general, something is said to be intrinsically valuable because it has value in and of itself, just by virtue of existing. Something that is valuable only in relation to something else, that is, valuable because it is needed to effect some goal or end, is said to be instrumentally valuable; it is an instrument to be used to do or obtain something else. Drugs, in and of themselves, have little or no intrinsic value; it is patients needing the drug that instantiates its value, because it is a means to health, pain relief, etc. No one will buy my $1,000 vaccine for the Purple Death because there is no such thing as the Purple Death. I probably could not get $1 for it because its only value is its utility to achieve some end. People, however, have intrinsic value; parents see their children as valuable because they exist, not what they can do. If person B needs compound A to live, and B is valuable in and of herself, whereas A is valuable only insofar as B cannot live without it, the only rational course of action is to give A to B. We might say B should have A.

A natural response is that A has other, attributive values; it is comprised of materials whose purchase costs money that allows others to sustain themselves and their families, and its production provides jobs upon which still other people rely to support themselves. That proposition can be justified on social contract grounds. However, doing so merely reinforces the claim that financial value of lifesaving drugs is properly understood in terms of the traditional costs of production Berenson referred to; the claim that medications have intrinsic value fails on the grounds that A has no value in and of itself. Importantly, the proposition that drug price should be parameterized to the value of the life it saves succeeds in one important respect: it denudes its direct parallel to ransom.

The other type of argument is best understood historically. It is therefore instructive to step back for a moment once again and look at medicine in general in the United States. American medicine developed into a profession with unusual independence from outside regulation, precisely what Big Pharma says it wants. [2534-35,72] It has been argued that at least part of that independence, perhaps a great deal, stems from physicians, as a profession, adopting a fiduciary duty to their patients. [1337-15] The longstanding practice of physicians not patenting therapeutic interventions (as was common in dentistry) is one example, and modern clinical bioethics provides others in the institutionalized values of beneficence, non-maleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice. [73] This has resulted in a field of endeavor in which practitioners have unusual latitude and discretion. [3779-145] Paul Starr goes so far as to use the word “sovereign” to describe the medical profession in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Social Transformation of American Medicine. [373-29] For the sake of both brevity and clarity, I will refer to the overall disposition towards patients as derivative of the physician’s fiduciary duty, understanding that duty has a specific definition and intended use. Nonetheless, the disposition I refer to is roughly encapsulated in the term.

Starr begins with an examination of what it means for something or someone to have authority. He points out that authority is related to control, and thus has a relationship to power, but argues, as Hannah Arendt does, that exercise of power is paradoxically a failure of authority. [379-10,74] Authority, “incorporates two sources of effective control: legitimacy and dependence. The former rests on the subordinates’ acceptance of the claim they should obey; the latter on their estimate of the foul consequences that will befall them if they do not.” [379-10] Medical care derives its legitimacy from its results, but not its results alone; even when results are poor, patients are willing to believe physicians are legitimate, merely unsuccessful, or unhelpful. A key component has been that in the United States, efforts of physicians to arbitrarily increase the rates they charge for the care they provide have historically been met with both public outcry and governmental intervention. Starr notes:

“A series of legal decisions shortly after the turn of the century effectively precluded the emergence of profit-making medical care corporations in most jurisdictions. Between 1905 and 1917, courts in several states ruled that corporations could not engage in the commercial practice of medicine, even if they employed licensed physicians, on the grounds that a corporation could not be licensed to practice, and that commercialism in medicine violated “sound public policy… These decisions were not models of rigorous legal reasoning… Respectable opinion did not favor “commercialism” in medicine.” [37204]

The latter point is important; while special interests undoubtedly have profound influence, a society’s values as a whole include ethical values. [1,6] Governmental regulation requiring labeling, safety testing, and the like have saved the pharmaceutical industry from itself, and as Starr notes, when the medical profession has strayed from its central duty, society has corralled it back in.

Competing Fiduciary Duties as a Cause of Drug Shortages

Nonetheless, pharmaceutical companies’ fiduciary duty is understood as to their stockholders, rather than the patients who rely upon their products to survive. The ethical issue is, at its basis, an assessment of whether these two fiduciary duties can meaningfully coexist as increasingly pharmacological interventions become standard of care, and whether the fiduciary duty to stockholders is justifiably absolute in the way the fiduciary duty to one’s patient is.

It should not be forgotten that most medications were developed at some point with public funds; roughly 75% of new molecular entities owe their existence to NIH funding. [75] Traditionally, acceptance of public funds has come with certain responsibilities. Such funding wasn’t made available by the government to make enterprising individuals rich, or even find the new discoveries or forge new interventions; public funding is made available for the purpose of bettering the public good.

One could say the government has a financial fiduciary duty to its citizens, which in the framework of the values the pharmaceutical industry endorses, would dictate reigning in what Big Pharma can do so as to provide a better return to the citizens. It is not at all clear that the wealth of the entrepreneur is a necessary component of that process, as one can imagine a non-profit pharmaceutical company just as easily as a group of physicians volunteering their skills. Rather, it seems that the use of public funds to develop marketables that end up in the hands of Shkreli and others like him is proof that reform is needed, and justified by having furnished the means of development to begin with. It also appears this can be validated without resort to bioethical values; the industry’s own values suffice.

Given this, it seems some form of government intervention is necessary. Physicians have been largely self-policing, and thereby escaped the bureaucratic infiltration of regulatory frameworks present in industries such as banking and stock trading. The pharmaceutical industry, by both their historical actions and the increasing degree of harm rendered by unethical practices that thus far have no legal remedy, seems overdue for reconsideration. There have been many proposals regarding how to improve the pharmaceutical industry. Some options include encouraging the insurance companies to pay higher prices for drugs that treat rare conditions, or subsidizing those that have little prospect of financial return. Some have even been legislated: the Bayh-Dole Act allowed private corporations to patent publicly funded research, but it also gave the government the power to cap prices – a power hasn’t exercised on even a single drug. [75]

Perhaps the best place to start is the creation of a fiduciary duty to the patient that follows all work done with, or made possible by, public resources. Some mechanism is needed by which decisions made regarding drug production and pricing are based not solely on a (financial) fiduciary obligation to stockholders, but on the medical profession’s fiduciary duty to patients. There was a time when physicians, as a group, were able to reign in the excesses of the pharmaceutical industry, and require ingredients be disclosed, and direct advertising to patients stopped. [37127-140] A contemporary effort of the like seems overdue. And while the pharmaceutical industry lacks the social authority that undergirds medicine, and thus lacks the foundation of trust medicine enjoys, medicine would do well to countenance the inversion of that state of affairs; insofar as it flirts with disestablishing its fiduciary bindings, so too may its authority wane.

The author has disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Stowe Locke Teti

Executive Editor,

Pediatric Ethicscope: The Journal of Pediatric Bioethics

Clinical Ethics Coordinator and

Director of Ethics Education

Children’s National Health System

111 Michigan Avenue NW

Washington DC 20010

steti@childrensnational.org

Endnotes

1 Lipworth W, Kerridge I. Why drug shortages are an ethical issue. Australasian Medical Journal. 2013; (6)11: 556-9. 2 Oppenheim FE. Moral principles in political philosophy. Random House. New York. 1968: 8-9

2 Oppenheim FE. Moral Principles in Political Philosophy. Random House. New York. 1968; 8-9.

3 For a general overview, see Value Theory. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 28 Jul 2016. Online at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/value-theory/. Accessed 28 Dec 2016.

4 See generally Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Trans G.E. Anscombe. New York. 1958. See also p. 126 for discussion of aesthetic judgments as “language games.”

5 Schweitzer SO. How the US Food and Drug Administration can solve the prescription drug shortage problem. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):e10-4.

6 Singleton R, Chubbs K et al. From framework to frontline: Designing a structure and process for drug supply shortage planning. Healthcare Management Forum. 2013 Spring;26(1) :41-5. Online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1016/j.hcmf.2012.11.003

7 Berenson A. A Cancer Drug’s Big Price Rise is Cause for Concern. The New York Times. 12 March 2006. Accessed 19 December 2016.

8 Online: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm. Accessed 19 December 2016.

9 Johnson LA. “Hospitals coping better as drug shortages persist.” Associated Press. 27 Feb. 2014 @ 8:51 PM EST. Accessed 19 December 2016.

10 American Academy of Pediatrics. Department of Federal Affairs. Drug Shortages in Pediatrics: Data from AAP Member Survey. Feb. 2016.

11 Unguru Y. Shortages of Drugs: Surpluses of Ethical Challenges. Pediatric Ethicscope. 2017 Fall; 29(1): 18-26.

12 Kehl KL. et. al. Oncologists’ Experiences with Drug Shortages. Journal of Oncology Practice. Mar 2015. 19 December 2016.

13 Drug Shortages in Pediatrics: Data from AAP Member Survey. American Academy of Pediatrics Department of Federal Affairs. Feb. 2016. Accessed 19 December 2016.

14 Fink S. Drug Shortages Forcing Hard Decisions on Rationing Treatments. The New York Times. 29 Jan 2016. Accessed 19 December 2016.

15 Koba M. The U.S. has a drug shortage–and people are dying. Fortune. 6 Jan 2015 6:01 AM EST. Accessed 19 December 2016.

16 Stein R. Shortages of key drugs endanger patients. The Washington Post. 1 May 2011; Online: www.washingtonpost.com/national/shortages-of-key-drugs-endanger-patients/2011/04/26/AF1aJJVF_story.html?hpid=z5. 16 December 2016.

17 Wagner J. Should the pharmaceutical industry be a regulated utility? Health Affairs. Jan 2005;24(1):289-290.

18 Ventola, CL. The Drug Crisis in the United States. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2011 Nov; 36(11): 740-742, 749-757.

19 McLaughlin M et al. Effects on patient care caused by drug shortages: a survey. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. Nov/Dec 2013; 19(9):783. Online: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=17307. See also Unguru, Yoram. Shortages of drugs, surpluses of ethical problems. Pediatric Ethicscope. 2017 Fall; 29(1): 18-26.

20 Analysis finds shortages increased U.S. hospital costs by an average of $230 million annually. Premier Press Release. Premier, Inc. 27 Feb 2014. Online at: https://www.premierinc.com/drug-shortages-continue-pose-patient-safety-risks-challenge- providers-according-premier-inc-survey/. Accessed 28 Dec 2016.

21 Mangum B. FDA Drug shortages workshop. Premier Healthcare Alliance. Slide 7,8. Online: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM274586.pdf. Accessed 9 Jan 2017.

22 Premier healthcare alliance. FDA Drug Shortages Workshop. 2011. Online at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM274586.pdf. Accessed 19 December 2016.

23 Prescription drug spending is expected to rise 22% over the next five years; see Rosin, Tamara. 17 Statistics on the current state of U.S. healthcare spending, finances. Beckers Hospital Review. 13 Sept 2016. Online at: http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/17-fascinating-statistics-on-the-current-state-of-us-healthcare-spending-finances.html. Accessed 29 December 2016.

24 United States Government Accountability Office. Drug Shortages: Public health threat continues, despite efforts to help ensure product availability. GAO-14-194 Drug Shortages. Feb 2014. http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/660785.pdf. Accessed 29 December 2016.

25 Angell M. The Truth About the Drug Companies. Random House. New York. 2004.

26 Pediatric Oncology Working Group makes only indirect reference to the values conflict See DeCamp et al. Chemotherapy Drug Shortages in Pediatric Oncology: A Consensus Statement. Pediatrics. 2014;133. e718, Recommendation 1, Background: “Working with the Department of Justice to… report exorbitant pricing.” And See e722, Recommendation 6, Action Item 1: “emphasizing transparency as a value in planning processes, including financial analyses” (at e722).

27 S. Schweitzer attributes shortages to 3 things: consolidation of generic market; increased penetration of generics; increased dependence on outsourced drug products. See Schweitzer, Stuart O. How the US Food and Drug Administration can solve the prescription drug shortage problem. American Journal of Public Health. May 2013; 103(5): e10-314.

28 Compare: Angell M. The truth about the drug companies. Random House. New York. 2004. With: Perkins, Lawrence. Commentary: Pharmaceutical companies must make decisions based on profit. West J Med. 2001 Dec; 175(6):422-23.

29 Perkins L. Commentary: Pharmaceutical companies must make decisions based on profit. West J Med. 2001 Dec; 175(6):422- 23.

30 Pear R. Research costs for new drugs said to soar. The New York Times. 2001 Dec 1;C1. Online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/01/business/research-cost-for-new-drugs-said-to-soar.html. Accessed 12 Jan 2017. Cited in: Angell, Marcia. The truth about the drug companies. Random House. New York. 2004: 39.

31 Compare Herper M. The truly staggering cost of inventing new drugs. Forbes. 10 Feb 2012 at 7:41 AM. Online at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewherper/2012/02/10/the-truly-staggering-cost-of-inventing-new-drugs/. Accessed 12 Jan 2017. With Ramsey, Lydia. Pharma companies’ no. 1 justification for high drug prices is bogus. Business Insider. 9 Dec. 2015, 12:53 PM. Online at: http://www.businessinsider.com/research-and-development-costs-might-not-factor-into-drug-pricing-2015-12. Accessed 12 Jan 2017.

32 See generally Charon Rita, Montello Martha, eds. Stories matter: The role of narrative in medical ethics. Routledge. New York. 2002.

33 Porter R. The greatest benefit to mankind: A medical history of humanity. W.W. Norton. New York. 1997. 368, 663-4. In Shah Sonia. The body hunters: Testing new drugs on the world’s poorest patients. The New York Press. New York. 2006:37, 192 (Note 4).

34 See Levine C. Has AIDS changed the ethics of human subject research? Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics. Sep 1988;16(3- 4): 167-73. See also Marshall, Mary Faith. Born in scandal: The evolution of clinical research ethics. Science. 26 April 2002 8:00 AM. Online at: http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2002/04/born-scandal-evolution-clinical-research-ethics. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

35 Shah S. The body hunters: Testing new drugs on the world’s poorest patients. The New York Press. New York. 2006:37, 192 (Note 5) citing Hilts, Philip J. Protecting America’s health: The FDA, business, and one hundred years of regulation. Alfred A. Knopf. New York. 2003:46,53.

36 Shah S. The body hunters: Testing new drugs on the world’s poorest patients. The New York Press. New York. 2006:37-38

37 Starr P. The social transformation of American medicine. Basic Books, Perseus Books Group. 1982: 335.

38 Hilts PJ. Protecting America’s health: The FDA, business, and one hundred years of regulation. Alfred A. Knopf. New York. 2003:121-130. See in Shah Sonia. The body hunters: Testing new drugs on the world’s poorest patients. The New York Press. New York. 2006:39, 193 (Note 16).

39 37 CFR Chapter IV Part 401. Rights to inventions made by nonprofit organizations and small business firms under government grants, contracts, and cooperative agreements. Online at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/37/part-401. Accessed 29 December 2016.

40 Boettiger S, Alan B. Bayh-Doyle: if we knew then what we know now. Nature Biotechnology. 2006; 24: 320-323.

41 Munos B. New drug approvals hit 18-year high. Forbes. 2 Jan 2015 @ 1:40 PM. Online at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmunos/2015/01/02/the-fda-approvals-of-2014/. Accessed 2 Jan 2017.

42 Temple R. Comparative effectiveness approaches not always the most effective. United States Food & Drug Administration. 26 Feb 2016. Online at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/NewsEvents/ucm336185.htm. Accessed 29 Dec 2016.

43 Nowell P. Discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome: a personal perspective. J Clin Invest. 2007 Aug 1; 117(8): 2033-2035.

44 Dreifus C. Researcher behind the drug Gleevec. The New York Times. Science Section. 2 Nov 2009. Online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/03/science/03conv.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2017.

45 2009 Lasker Awards. Molecularly targeted treatments for chronic myeloid leukemia. Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation.

46 Druker, BJ, Talpaz, M, Resta, DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344;1031-37.

47 Berkrot, Bill. Success rates for experimental drugs falls: study. Reuters. Feb 14 2011 @ 8:09 AM EST. Online at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-pharmaceuticals-success-idUSTRE71D2U920110214. Accessed 3 Jan 2017.

48 Aitken M, Ernst B, Cutler D. Prescription drug spending trends in the United States: Looking beyond the turning point. Health Affairs. Jan/Feb 2009; 28(1): w151-w160.

49 Ro S. Here are the profit margins for every sector in the S&P 500. Business Insider. 16 Aug 2012. Online at: http://www.businessinsider.com/sector-profit-margins-sp-500-2012-8.

50 Williams S. Seven facts you probably don’t know about Big Pharma: Big Pharma companies are truly in a class of their own. Forbes. 19 July 2015 @ 9:06AM. Online at: http://www.fool.com/investing/value/2015/07/19/7-facts-you-probably-dont-know-about-big-pharma.aspx. Accessed 29 Dec 2016.

51 Anderson R. Pharmaceutical industry gets high on fat profits. BBC News. 6 Nov 2014. Online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/business- 28212223. Accessed 1 Jan 2017.

52 Applby J. Hospitals, patients run short of key drugs. Health & Science. USA Today. 11 July 2001. Online at: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/2001-07-11-drugs-usat.htm. Accessed 29 Dec 2016.

53 Tolstrup J, Olesen PH, Kronborg MV. Lundbeck’s acquisition of Ovation Pharmaceuticals cleared by US Federal Trade Commission. Lundbeck press release. 19 Mar 2009. Online at: http://investor.lundbeck.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=608630. Accessed 5 Jan 2017.

54 Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation archive of Lundbeck press release. www.clfoundation.org. Access at: http://www.clfoundation.org/sites/default/files/content/MUS009_MD%20Letter_Mustargen%20Availability_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 19 December 2016.

55 2015 Recordati Financial Statement reads: “Recordati’s proven ability to generate profitable alliances with prominent players in the pharmaceutical industry is the basis of an increasingly intense activity…”

56 United States Government Accountability Office. Drug Shortages: FDA’s Ability to Respond Should be Strengthened. GAO- 12-116. Nov. 2011. http://www.gao.gov/assets/590/587000.pdf. Accessed 16 December 2016.

57 Markowski ME. Drug shortages: The problem of inadequate profits. Harvard Law School. Apr 2012. Online at: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11940215 Accessed: 8 Jan 2017.

58 Lundbeck 2012 Annual Report.

59 Howard P. To lower drug prices, innovate, don’t regulate. New York Times. 23 Sept 2015 @ 3:30 AM. Online at: http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/09/23/should-the-government-impose-drug-price-controls/to-lower-drug-prices-innovate-dont-regulate. Accessed 2 Jan 2017.

60 Sharma A. Orphan drug: Development trends and strategies. J. Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010 Oct-Dec; 2(4): 290-99. See also What is an orphan drug? www.orpha.net. 16 December 2016. http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Education_AboutOrphanDrugs.php?lng=EN

61 Economic analysis of the causes of drug shortages. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. ASPE, Dept. Health & Human Services. Oct 2011. Online at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/108986/ib.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2017.

62 Allwood M. Assessing the shelf life of aseptically prepared injectables in ready to administer containers. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2012; 19: 277.

63 Kantarjian, HM. Chemotherapy drug shortages: A preventable human disaster. American Society of Clinical Oncology Post. 15 Nov. 2011. Online at: http://www.ascopost.com/issues/november-15-2011/chemotherapy-drug-shortages-a-preventable-human-disaster.aspx Accessed: 12 Jan 2017. Cited in: Markowski, M.E. Drug shortages: The problem of inadequate profits. Harvard Law School. Apr 2012. Online at: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11940215 Accessed: 8 Jan 2017.

64 Freundlich N. Keep the focus on rising drug prices, not smirking Shkreli (February 8, 2016). http://reforminghealth.org/2016/02/08/keep-the-focus-on-rising-drug-prices-not-smirking-shkreli/ Accessed 2016 Mar

65 Collins S (R-ME), McCaskill C (D-MO). United States Senate Special Committee on Aging. Sudden price spikes in off-patent prescription drugs: The Monopoly Business Model that Harms Patients, Taxpayers, and the U.S. Health Care System. Online at: http://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Drug%20Pricing%20Report.pdf. Accessed 9 Jan 2017.

66 U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Understanding recent trends in generic drug prices. ASPE Issue Brief. 27 Jan 2016. Online at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/understanding-recent-trends-generic-drug-prices. pp. 11. Accessed 28 December 2016.

67 Eunjung CA. U.S. lawmakers demand investigation of $100 price hike of lifesaving EpiPens. Washington Post. 23 August 2016. Online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2016/08/23/u-s-lawmakers-demand-investigation-of-100-price-hike-of-life-saving- epipens/?utm_term=.9ba35130c0f5

68 Schumock G et al. National trends in prescription drug expenditures and projections for 2016. American Journal of Health- System Pharmacy. May 2016. ajhp160205

69 Johnson, CY. Documents detain price hike decisions by former Turing CEO ‘Pharma bro’ Shkreli. Chicago Tribune. Business. 2 February 2016 10:04PM.

70 Chen C. Drug Industry Group starts ad campaign to defend pricing. Bloomberg. 6 Sep 2016 @ 9:00 AM EST. Online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-09-06/drug-industry-group-starts-ad-campaign-to-push-back-on-pricing. Accessed 8 Jan 2017.

71 Costs in Context: Benefits of medicines to the patients, the health care system, and the economy. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Online at: http://www.phrma.org/advocacy/cost-and-value. Accessed 9 Jan 2017.

72 Popeo, DJ. A New FDA? Op-Ed. The New York Times. 16 Dec 2002.

73 Limentani, A. The role of ethical principles in health care and the implications for ethical codes. J. Med. Ethics. 1999; 25:394-398.

74 Arendt, H. What is Authority? 1954:2. Between Past and Future: Six Excercises in political Thought. Viking Press. New York; 1961. Online at: http://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/330T/350kPEEArendtWhatIsAuthorityTable.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2017. See also Authority in the Twentieth Century. The Review of Politics. Oct 1956; 18(4) 403-417.