There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

Offering sanctuary to those fleeing war is a pressing human rights issues in the world today. Globally, there are currently 25.4 million people forced to leave their home to seek safety. Half of these people are children. Despite these staggering statistics, governments seem to have ignored their duty of care to children.

Legal and social precedent support broad parental discretion in the absence of immediate and severe endangerment of the minor’s welfare. However, in many cases of maltreatment, suspected or substantiated, parents retain PDM rights. The possibility of a guardian who is both surrogate and cause of harm threatens the conventional decision-making model; this paper offers an analysis of the primary challenges and shows that many of the ethical questions arise as the decision-making process unfolds and information is gathered.

This article highlights the importance of psychological and medical evaluations for asylum seekers in the United States, and identifies physicians and other healthcare professionals as uniquely situated for this work. This paper outlines the benefits and drawbacks to such evaluations and addresses their utility in immigration law, ultimately calling for increased clinician involvement in pro bono evaluations.

In recent years, the unique role of medical professionals in the asylum adjudication process has been thrown into sharp relief as asylum applications surge, with over one million pending cases backlogged in the U.S. asylum system as of August 2019. Medical evaluations dramatically increase the likelihood of an individual obtaining asylum. The author examines the role medical trainees play in this process.

How did we get here? Mara, now nearly 17-years-old, was born with a neurogenic bladder. Up until two years ago, she was a model patient. No one worried about her adherence with self-catheterization or medications. She was optimistic about her future, cared about her health, and we looked forward to her bright and open future. But now Mara says,

“I don’t care.”

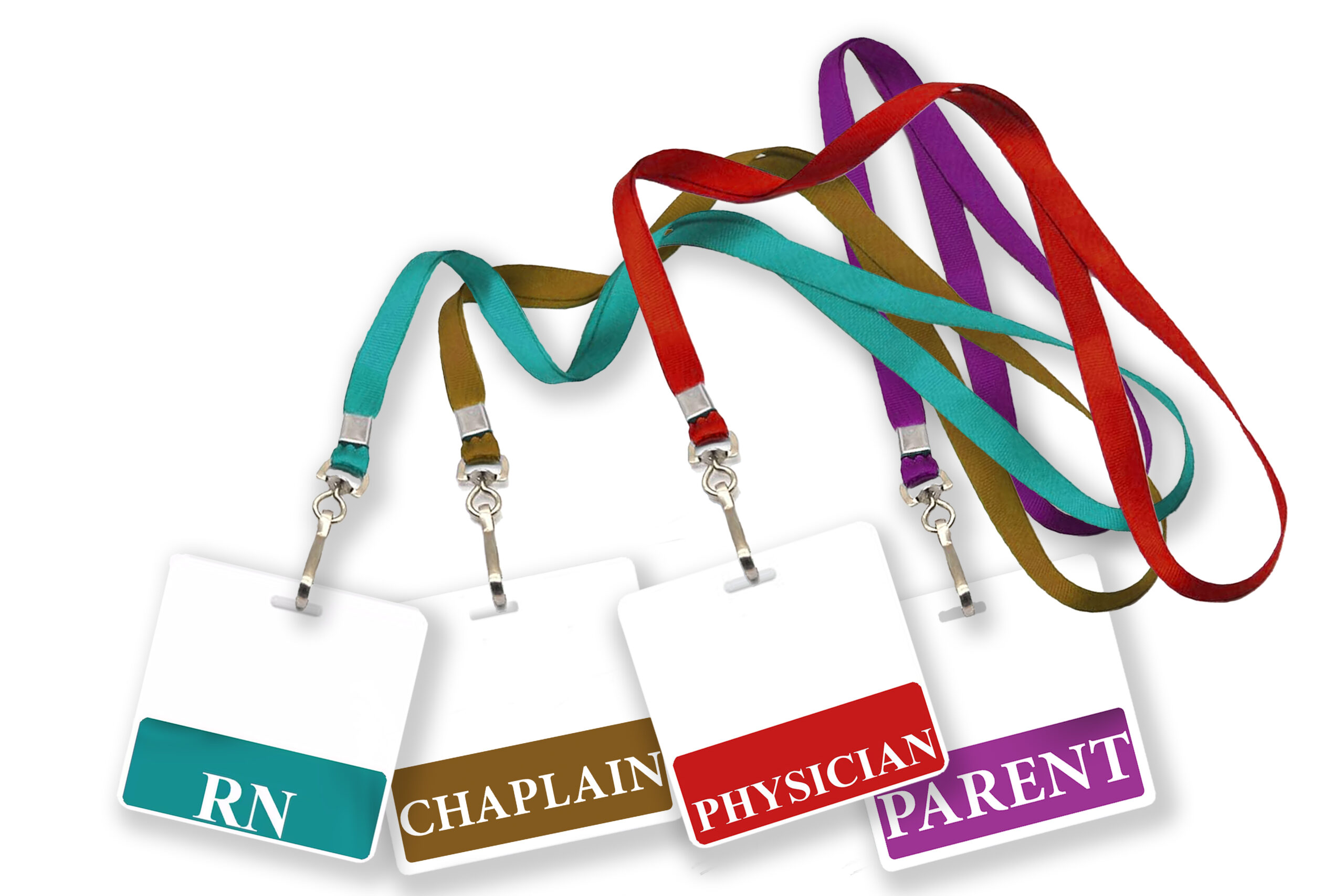

Medical futility is often a point of debate in situations of hoping for an unlikely outcome, or a condition with a treatment that necessitates high levels of pain or discomfort. Anencephaly is generally accepted as incompatible with prolonged life, with few infants surviving into the neonatal period. Parents are typically counseled accordingly, resulting in pregnancy termination or comfort care after delivery. This case report examines the ethical considerations involved in the decision to continue life-prolonging treatment of an 8-month-old infant with anencephaly.

Ethiopian physicians, nurses, and midwives routinely encounter cultural challenges created by language barriers, an urban vs rural divide, and differences in education that impact the patient-provider relationship. Despite limitations in personnel and resources, these clinicians have devised approaches to overcome these barriers to best serve their patients.

“Suffering” is a concept that is frequently invoked in discussions about medical decision-making in pediatrics. However, empirical accounts of how the term is used are lacking, creating confusion about the concept and leaving parents and providers unsure about the appropriate ways to account for it in pediatric decision-making. We conducted a qualitative content analysis of pediatric bioethics and clinical literature in selected journals from 2007 to 2017 to determine how authors define and operationalize the term when referring to issues in pediatric treatment.